Research Project: IN SEARCH OF PRACTICE _ Part 1

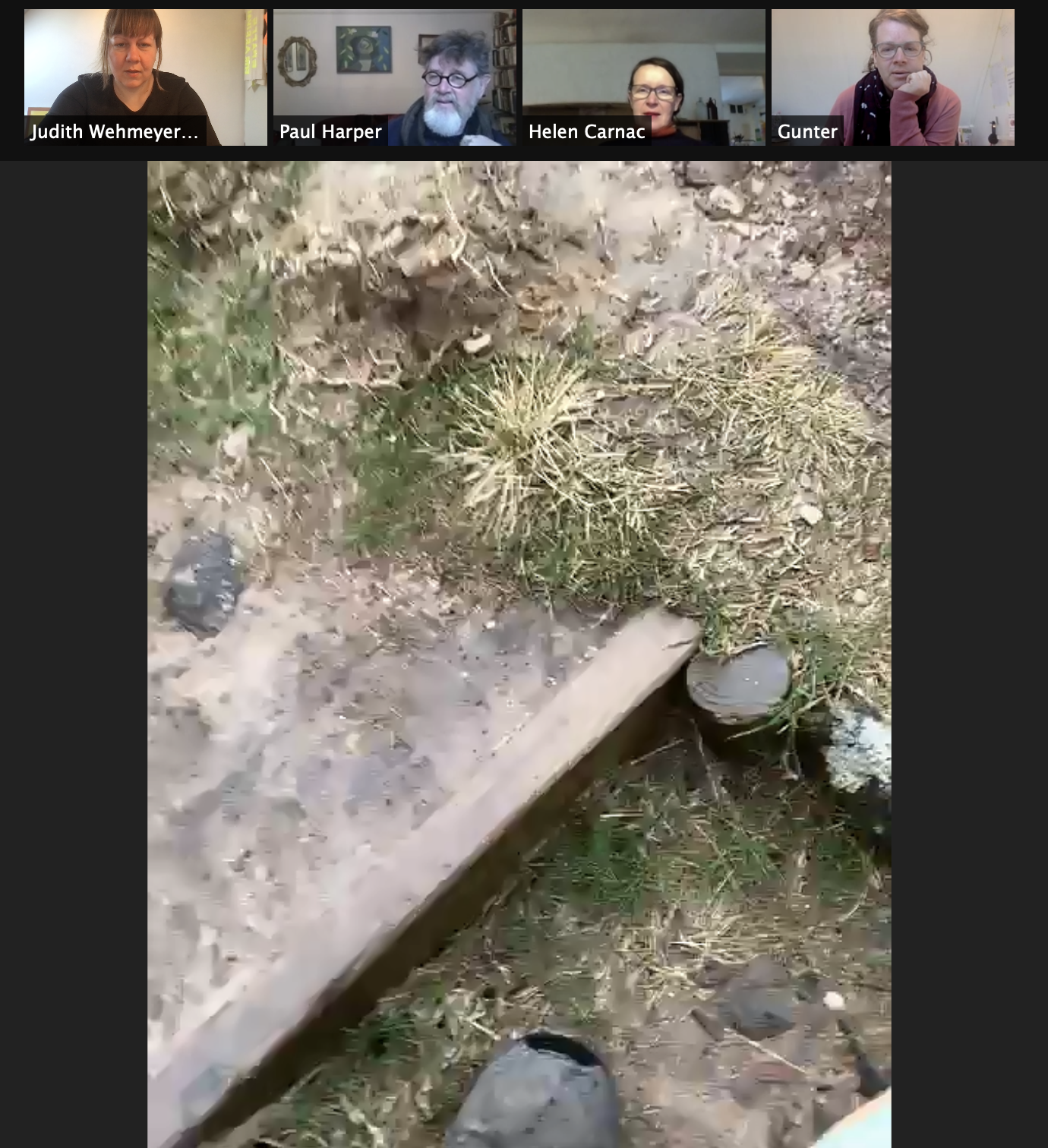

PRACTICE FOR BREAKFAST _CONVERSATIONS AROUND THE DIGITAL TABLE

Research Collaboratory: Emily Luce, Paul Harper, Helen Carnac, Fabrizio Cocchiarella, Judith van den Boom, Tess Wehmeyer.

08.30 GMT, UK

09.30 +1GMT, NL

23.30 -8GMT, CAN

________

Over the coming months we will be sharing parts of conversation that took place during IN SEARCH OF PRACTICE

A series of dialogues set over 3 days in spring 2021, bringing practice, theory, outdoor and indoor together. Below two parts reading of a long documentation.

________

Introduction 1

Dawn and dusk have passed. The sun rotates and greets a group of practitioners coming together around the digital table. Logging in from different parts of the world ‘In Search of Practice’ forms a reflective dialogue. Drawing together a stream of thought, doubt and search to contemplate the agency of design. The group makes a small inquisitive drift that, through a digital body investigates values and approaches for practice. In Search of Practice is developing as a conversation, bringing together experience, literature and documentation that invigorates. Connecting and fostering a new perspective, collective inquiry and drawing out critical parameters.

A collective inquiry also took place in 2019 when ‘In Search of Practice’ hosted by UFƟ Design Collaboratory initiated a physical drift in London. A group of makers and researchers came together to share views on practice through intentional wandering. The drift moved through the environment connected by words and actions, sharing present and history, and spontaneous encounters with nature, urban, and habitants.

Anno 2021 In Search of Practice has never been more timely. For over a year, Covid19 moved into all our lives, shifting practices indoors, turning living spaces into workspaces, impacting the felt synergy of being together. It prompted the practice to pause, suspend, or reinvent, making the absence of physical, material, and social connection noticeable. This pause evoked a deep longing to connect and share a more sensitive approach. Reviewing the tools, experiences and rhythms of practice and set new intentions on what matters in how we build our practices.

________

Introduction 2

Around the table. A state of confusion. Embodiedness. Traveling into wilderness. Radical bodies.

Helen: I’ve just come inside.

Judith: It was cold outside there, no?

Helen: It’s quite chilly.

Paul: Now, well, it’s nice to see everyone.

Judith: And we have someone who I know very well but who you might not know, is Emily. She’s is in the past on Vancouver Island. So what is, 11PM at night?

Emily: It’s 23.30. Glad to see everything’s okay in the future.

Fabrizio: Yes! We’re still here.

Judith: We’re still fresh awake. We’ll send the sun over in about ten hours and you’ll be in the light again to enjoy the dawn. I’m really happy everybody’s around this digital table, we haven’t seen each other in a long time. Let’s do a round who is who and where we’re based, from night owls to morning birds, a small introduction.

Emily: Hi, everybody. It’s really nice to meet you all after hearing about you for a few years. We’re here in Hupač̓asatḥ Territory on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and I’m an at-large artist and graphic designer. ( Emily is colliding worlds by working with her partner and artist Rodney Sayers on www.searchandresearch.net and [ C.R.A.F.T. ], read more on www.craftpeople.ca )

Gunter: I’m located in the Netherlands, and probably you would describe me as an innovation urbanist, focussed on nature experience, flourishing with nature. I’m doing a PhD in and looking how can we flourish with nature and apply this to emerging design practice. That’s me in a nutshell, and I’m giving over to Paul. ( Gunter is part UFƟ and working on www.departmentofwilderness.com )

Paul: Okay, I’m based in Somerset, and I teach critical and contextual studies to art and design students and I write about art. And I finished my PhD actually a long time ago now it seems, about eight years ago, but in my PhD I was trying to understand the nature of the making experience and how it contributes to meaning. So that’s me. Well, I’m going to hand over to Fabrizio. ( What Paul also does is, combining writing, teaching, research and consultancy in the visual arts and crafts)

Fabrizio: Yeah, thank you. So, gosh—

Judith: Sum it up.

Fabrizio: Bloomin’ ’ell. Flippin’ ’eck! Well, I’m up north in UK and I’m doing a PhD—well, I have been doing it—which has been paused recently and I think probably more recently I’ve been asking myself what am I doing?! ( Fabrizio is part UFƟ, and re-inventing ways of looking at and experiencing our relationship with the physical (and metaphysical) through ‘para-design’, more to read on www.para-design.org )

Paul: Asking that question is one of the crucial phases.

Fabrizio: Especially with all this craziness that’s been going on. I mean, I teach at Manchester School of Art. I teach interior design. I do research. I’m a designer. And I think this has been really nice platform to talk with, to kind of think about how you position yourself differently and don’t get lost in the institute, and start to think kind of more broadly about things and test those ideas out. Over to Helen.

Helen: I recently relocated to Somerset, into a very rural place, from London, and it’s fantastic and it’s giving me lots of time—well, I don’t know about time, but space to think about what I’m doing. Because unlike—most of you know—I don’t work in the universe anyone, I’m not doing a PhD, and I’m going it alone and I’m finding out what it’s like to do things without all of that background—well, I’ve got the background without all of that structure. ( What was said, but essential, Helen runs a environmentally grounded practice and is a reflective maker, finding connections between material, process and maker helencarnac(dot)wordpress(dot)com)

Fabrizio: It sounds lovely.

Helen: Yeah.

Judith: Oh, that’s okay. But I like what you said, Helen, without the structure. And, well, most of you know me, as we connect through practice and university. It looks a bit like we have a PhD pool, but that’s not the reason why we’re coming together. ( what she didn’t mention is, Judith is part UFƟ, part ArtEZ design department and working on departmentofwilderness.com )

but I thought a bit what you said, Helen, and its actually essential. Like that we’re all shifted out, and what Fabrizio said, coming to a state of confusion on what practice is. I think the confusion might be actually essential to get to a better understanding of it. I just hope that maybe in this session we can build on questions and just see what comes through. What sticks at the end of the session? And what could we take to the next time?

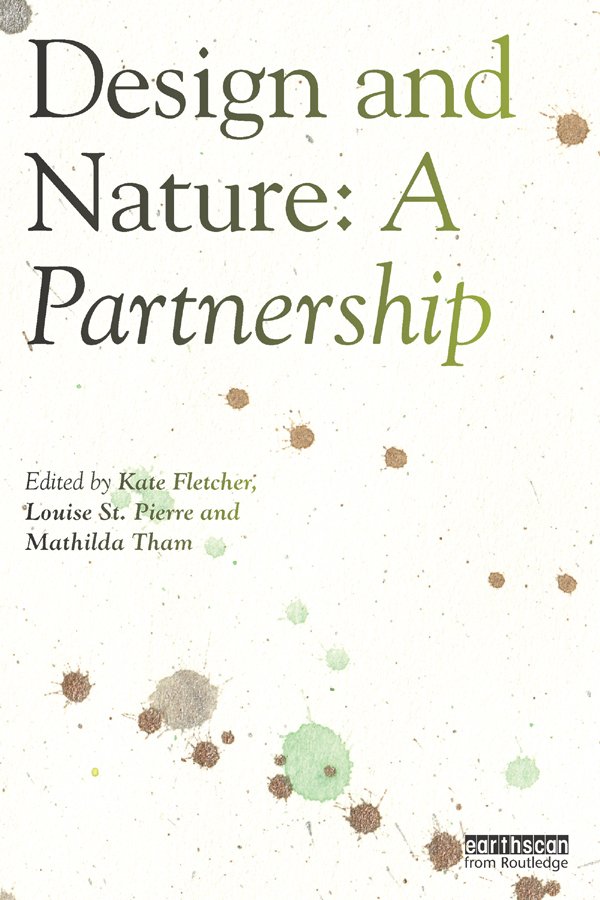

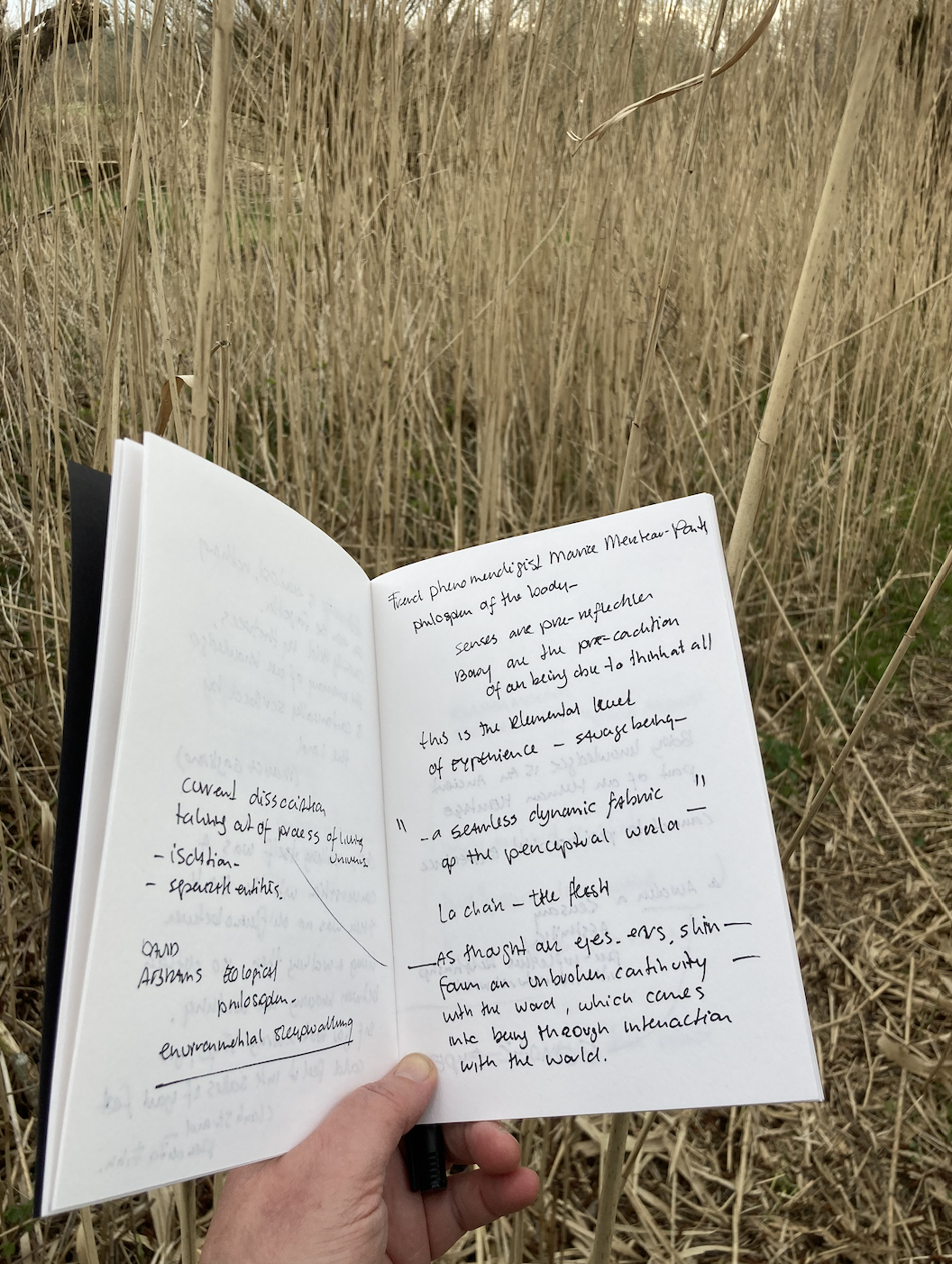

And so I got a book that I wish to share.

Emily: Take it away.

Judith: So it’s this book, Design and Nature: A Partnership, and I’ve been using it quite a bit also in my writing and reading. It’s written by Kate Fletcher, Louise St Pierre, Mathilda Tham, by Erskine. This book is a collection of essays from artists who are exploring this dialogue with nature. I wanted to share this not for the specific essays but more how its build it up. Created four chapters, basing this relationship of being embodied and connected wit nature through the positioning of the body.

There are four chapters: lying, sitting, standing and walking —oh, there’s still some lavender in between because I was reading it in summer. Lying is a very important mode for the body because it’s the area where you receive, it speaks of vulnerability due to laying down on the earth. How do we perceive from that? I know many of you walk and use it as a method. You become connected and actively engage, another way for listening. For me this is essential as often in practice we dismiss our body in our engagement.

The body as a tool. Especially when I think after this whole year of maybe even being online too much is this kind of—the body has sometimes been put aside. And it’s that after a year of online practice, its created confusion, and detachment with the world. I wish to return to my body being an ethnographic tool of being and receiving.

And I know some of you—I know Helen and Paul also are very much walkers too, almost like a form of practice. As a way of thinking, but it’s also a way of practicing, and I’m just really curious what everybody’s thinking about this.

Paul: I—I—

Fabrizio: I think it’s—

Paul: We both start talking! You go first, Fabrizio.

Fabrizio: I was going to say I don’t know about everyone else but I probably spend more time in nature this year. You know, with kind of working from home and lockdown it kind of becomes a place to get out the house, you know, just very simply just to get out and to—and certainly kind of living in the countryside or on the end of the countryside it’s—I think probably this last year I’ve had a different relationship with travelling. You know, rather than travelling to the city I’m travelling into the wilderness.

You know, sort of what you were talking about, perhaps different types of spaces make us think differently and provide different inspiration. And there’s certainly a shift I think in thinking we need to spend time in different environments.

Judith: Paul, what are you thinking?

Paul: Well, I’m just now thinking about what Fabrizio said! And actually where I live I live in a town which is a small country town and one of the things I really like about walking is the way you—when I walk around this area I kind of I’m constantly moving between the countryside and these kind of fringes of urban dwelling and I really like that. I really like discovering little hamlets and communities that are kind of tucked away off the main roads and I like the way they form a kind of rhythm to a walk.

Judith: Fringes. This feeling of these things that you’re not sure if they belong there or if they were purposely there.

Paul: Oh, yes, yes, yes.

Judith: Domesticated nature and wilder parts are shifting together.

Paul: So what I was going to say was that this thing about being embodied is absolutely central, I think. we are embodied beings. in some ways—I’m going to touch on that—that’s how we know the world, through our bodies. And it seems like such a straightforward idea, but it’s actually radically—it’s radical in relation to the sort of dominant kind of idea about knowledge and that actually we’re essentially spirits, disembodied beings and our sort of highest inspiration is to transcend our bodies. But this is where we live and it’s how we encounter the world.

Judith: Using your body is almost a form of activism, purposely standing and acknowledging the presence that you have a body —the word of ‘disembodied spirits’ is triggering..

Paul: Actually what I’ve been doing this week is writing a couple of new lectures, and so I was in that kind of mode. I put together a little slide presentation! And I called it Digging With My Pen, which is kind of—it’s from one of my favourite poems by Seamus Heaney who wrote this wonderful poem called Digging where he describes himself sitting writing and he can hear his father digging outside. and he reflects. He remembers his grandfather digging for peat in Ireland. And it’s full of really beautiful evocative sounds and sensations that—well, I will read it.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked,

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

My grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

So that’s Seamus Heaney and it was given to me by my favourite uncle who was a bricklayer and an English literature lecturer, and I love the way it kind of makes this connection between doing and thinking.

References conversation

Kate Fletcher, (2020) Design and Nature, a partnership. Routeledge

Seamus Heaney, (1966) “Digging" from Death of a Naturalist. Faber and Faber

Calvino, I. (1992) Six Memos for the Next Millennium London: Jonathan Cape

_____

Introduction 3

Weather. Keep those eyes on the skies. Optical illusions. Electrical energy. Lost experiences.

Fabrizio: And especially talking about the weather. I mean, just sitting here—but it’s raining quite a bit. It’s blowing so hard, the wind— straight over this little place that I’m sitting in, so I’m just about dry enough!

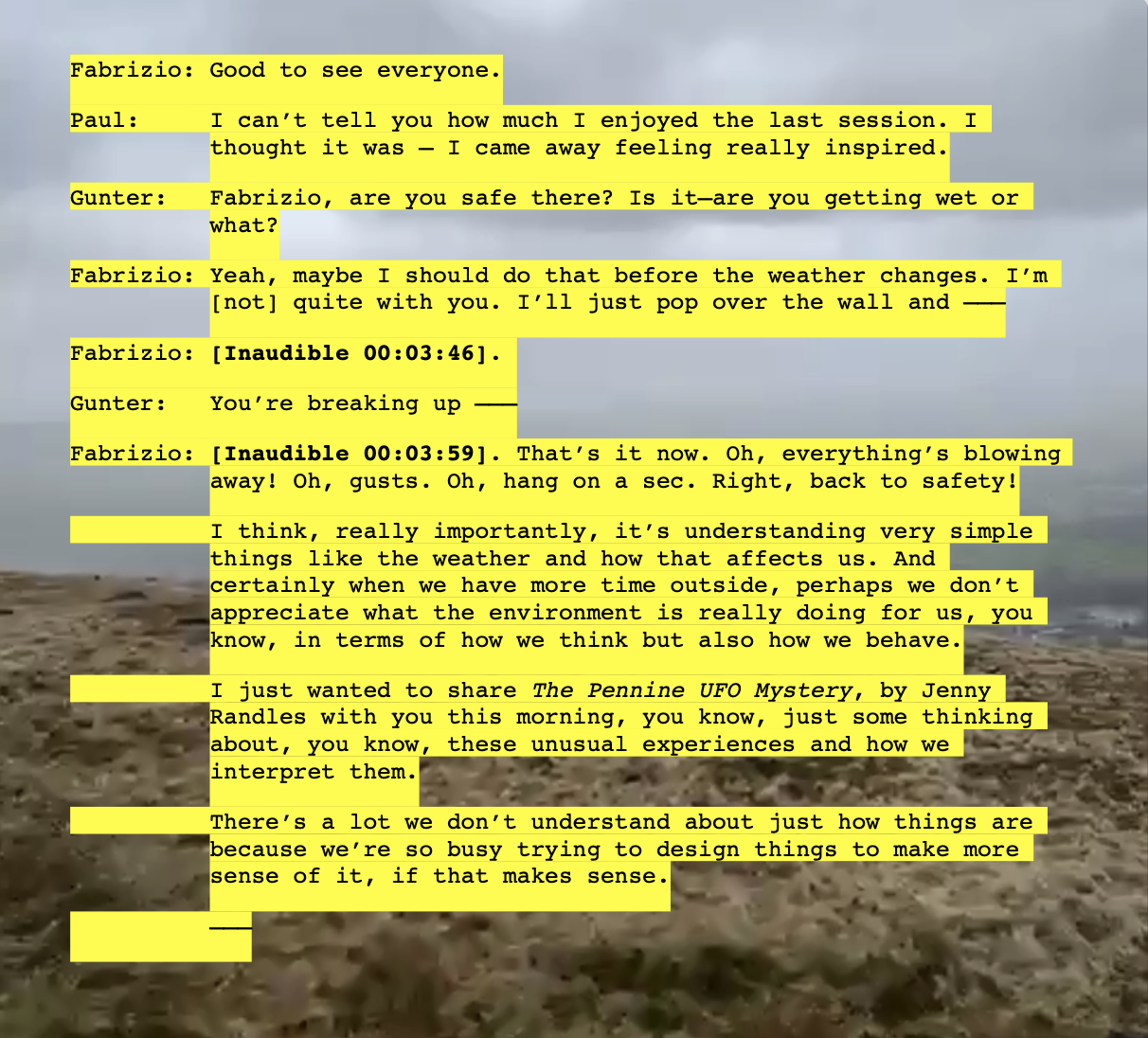

But what I’ll talk about is another little book, The Pennine UFO Mystery, by Jenny Randles. And there’s another little thing written in this book. Now, I met Jenny a few years ago at a conference. It was the LAPIS Paranormal Conference in Lytham St Annes. And I saw Jenny do a talk and it was—she’s quite a fascinating lady. She was really well-known in the Eighties reporting on UFO phenomena.

Jenny is from Yorkshire and she wrote in this book: ‘For Fabrizio. Keep those eyes on the skies.’ I’ve got some really rough notes that I made from her lecture, so I’m just going to read through some of those. So it’s going to be quite disjointed. And I’ll try to make sense of my notes in between all of that.

But Jenny used to kind of investigate phenomena around Todmorden and in the Pennines and kind of outside of Manchester and she started a group that used to meet at the Golden Lion and they used to get calls from people. I think certainly sort of late Seventies, early Eighties they used to get a lot of calls from people in the surrounding area of things at they’d seen and they used to go out and investigate. And Jenny got quite well known for doing this kind of investigation.

So the conference was in 2018, so a few years ago now. It doesn’t seem that long ago. Jenny was talking about optical illusions. She started off talking about optical illusions and about weather patterns and clouds and how we perhaps see things and interpret them in ways that we kind of we’ve heard about through stories or through things that we’ve seen through the media or on TV or in films. And she called them—she started off calling flying saucers — lying saucers and talking about them as optical illusions.

And she talked about how when you see something you can’t unsee it. It’s kind of to do with how you remember it and kind of links to what I was talking about last week, this kind of memory, and sometimes the things that you interpret aren’t always really what’s there.

Jenny talked about how flying saucers were first seen in the South Pacific and they were basically giant birds. People connected this with stories that they’d heard at the time about kind of UFO phenomena or it had just been the moon shining through a misty sky. Ordinary things. kind of unusual weather patterns as well that people kind of misinterpret.

She talked about UFOs as the opposite, so IFOs, so identified flying objects. And she kind of said that through her research she was able to identify about 95 percent of all UFO sightings as kind of attributed to unusual weather patterns.

So through time she talked about things. You know, in the Sixties perhaps satellites were seen as UFOs. In the Eighties there were a lot of UFO sightings because of laser technology and lights in the sky, particularly around Blackpool, that were seen miles away, that caused a lot of problems in the Pennines.

Anyway, [so these] sightings. Also reporting this kind of bending of space and time. And maybe this relates to what Gunter’s talking about also. Like maybe these experiences in nature—and a lot of these sightings happen in the hills and kind of natural environments—perhaps to do with unusual weather patterns or how that perhaps affects the body and makes us perceive time differently.

Things slow down.

She also talked about the US Air Force covered that —[inaudible 00:23:52] that they had with a — [inaudible 00:23:56].

Judith: You’re—

Fabrizio: There was an aircraft, a — [inaudible 00:24:02]

Judith: I think Fabrizio is being beamed up.

Fabrizio: Hello? Can you hear me okay?

Judith: Yes, we can now.

Fabrizio: Jenny called this kind of pause in time—and she’s known for talking about this and kind of coining the phrase—but she calls it Oz Factor, where sound disappears, you get an altered state of consciousness, and you have this kind of slip in time.

And she investigated a few particular phenomena around here, around Wilsden. And she said it changed over time. It used to be that people reported ghosts in this particular part of the countryside and then it became UFOs. And then when she investigated it she realised there was this really weird electronic energy in that area that would happen. It was kind of like electronic dumping.

So you could imagine with weather patterns how things perhaps—you know, or you could imagine how electrical energy from devices or through, you know, broadcasting kind of technology, how that could perhaps get collected in the atmosphere and then dumped in different locations. And apparently she kind of concluded that, you know, around here was a particular place where this kind of strange electrical energy would get dumped.

I think what was really fascinating listening to Jenny speak is you hear people talk about UFOs and, whether they believe what it is or not, or thinking about things beyond the Earth and beyond kind of our understanding of time. But also I think, really importantly, it’s understanding very simple things like the weather and how that affects us.

And certainly when we have more time outside, perhaps we don’t appreciate what the environment is really doing for us, you know, in terms of how we think but also how we behave. And, you know, if you get caught in these kind of unusual weather situations, perhaps how that can affect you in the long term.

It’s just started raining really badly!

But anyway, there’s lots more notes, but it’s kind of quite fragmented. But I think I just wanted to share that with you this morning, you know, just some thinking about, you know, these unusual experiences and how we interpret them.

Judith: Interesting relationship between experiences and weather it’s—what Gunter talked partialy about—is this mix of space and slowing down and coming to understanding. What we are seeing or experiencing, or—what bring belief systems, how we kind of—why do we need them? What do they bring us? How are they altering how we undertand life?

Fabrizio: Yeah.

Judith: When you talked about reminded me of Thin Spaces, a Celtic term, used to described experiences between Heaven and Earth, a kind of spiritual experience, or mesmerising. unable to explain. In this time it turned into a sense of alienness. What we not undertstand seems threatening.

Gunter: I really liked what you were talking about. Also I remember situations, even simple situations where you’re driving the car and you don’t hear any radio, you’re just driving a car, and suddenly you’re aware I have not looked at a road for the last ten minutes.

Fabrizio: Yeah!

Gunter: And you get this kind of shock. Whas my mind was on autopilot? A bit similar to déjà vu. That you kind of have an experience and then your mind kind of shuts off and you are in this state in between, and then you wake, you kind of come back to consciousness and something is missing or you feel something happened. And I think it’s also natural there. like I said, in nature there’s certain nature areas which can enforce this in a way somehow and that this sometimes unexplainable. But I think it’s also really, what I understand from you, is that kind of how your brain thinks and what you make out of it and how you—

Fabrizio: Yeah.

Gunter: —look for explanations to something unexplainable, yet—I mean—

Fabrizio: There’s—there’s—

Gunter: —not again are explained. Like we can explain how powerlines are affecting us or how wi-fi—couldn’t do this twenty years ago.

Fabrizio: Sorry, I was just going to say those lost experiences are maybe quite important. You don’t know that you’re there until you’ve had it. It’s that lost moment.

It tells us something about ourselves. If we weren’t present then, what was that time spent? Why is that lost, and how have we’ve been triggered in a way to forget or to lose kind of focus. But that loss of focus maybe is quite important. And I’m sure some cultures really value that quite differently.

References

Randles, J. (1983) The Pennine UFO Mystery. Granada publishers